János

SUGÁR

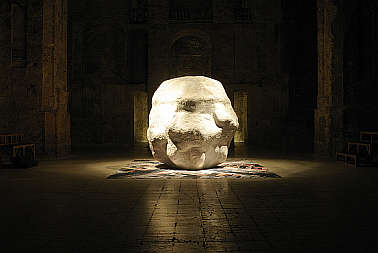

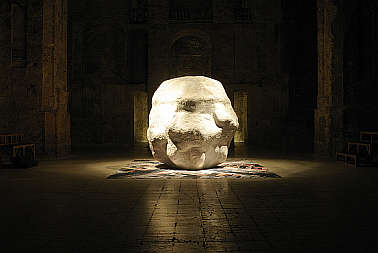

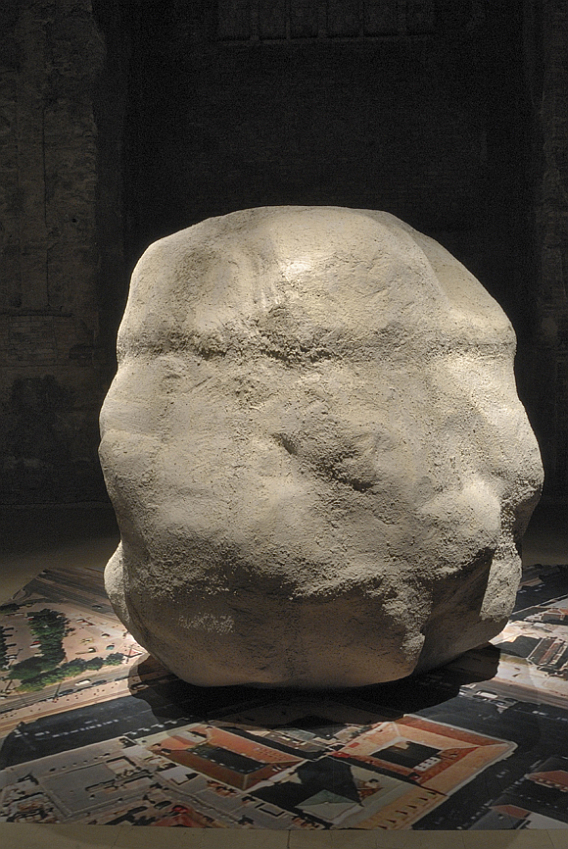

Fire in the Museum

Monument To The Rabble

Municipal Gallery / Museum Kiscell

Templespace

February 23–March 182012

Curated by Anikó B. Nagy

Ladies and

Gentlemen, let me state first that I am extremely honored to be allowed to speak

in the context of the opening of this exhibition. It is also a privilege to

share some of my thoughts concerning the project we are seeing here. I will

speak as an art critic from Austria with a strong interest in politics and

history and as somebody who has been paying attention, I studied Russian

cultural studies, to things happening in Eastern Europe and especially in the

former Soviet Union.

But let's return to Budapest which should be actually in „Central Europe". At least thats is the concept Austrian politicians fell in love some two decades ago, after the heroic dismantling of the iron curtain, for example after a small part of a fence close to Sopron was opened during a kind of picnic some Habsburgs had organized in that summer of 1989. It least we see that events on television every other year.

But just a last sidestep concerning the past before I speak about my reading of today's exhibition itself. We are here in a remarkable space which is also connected to our common history. This obviously used to be a church as a part of a monastery which abolished during the rule of Joseph II and his so called „Enlightened absolutism". Which was still absolutism, but nevertheless a major step forward in the political development of our region. I guess, if we speak about the Habsburgs at all, we should speak more about Joseph II and his political project of tackling mighty political and economic institutions such as the catholic church. Maybe this experience might still be useful.

As you might

know, János Sugár has been really trying hard to install a monument which kind

of does not want to be a monument. I do a agree with János that his planned fire

in the museum which should have been guarded and burning 24 hours during the

exhibition would have been a remarkable work of conceptual art. It would have

paid reference to the roots of mankind and the importance of fire, to Greek

mythology, to questions of solidarity, to the collective essence of memory. And

it would have been beautiful!

However, the Fire Department finally said no. Which is in fact not that surprising – I guess if you would try such a thing in any of our heavily regulated democracies, you might get a similar answer. And actually we should not forget, that Fire Departments are among the most powerful institutions of our times. For example, that's a part of my Russian experience, if a newspaper in Russia is facing political problems, it is usually not shut down by the police or the secret services. Somebody just sends a few firefighters and of course they find serious problems with safety regulations. And everybody is kicked out of the building.

However „Fire in the Museum" was not the end of János' endeavor with non-monuments or monuments which do not want to monuments as we know them. Paying reference to a statement by the radical leftist revolutionary of 1956, István Angyal, János Sugár proposed a big stone to commemorate the nameless scum of these events. Angyal had spoken about „a big rustic stone that should commemorate the nameless scum whence we came, with whom we have been one and shall return to our maker. But even this is foolish, as any fretting about the past. Forget us, forget us, that should help!

In the way we see this object right now, in it's reduced form depicting only a stone and nothing more, with no additional information on the surface, it is of course a critical work of art that is primarily referring to memory. And of course, due to the fact that we know Angyal's quotation, it might also related to a certain extent to the historic events of 1956. But János has also another idea: He would like to have the „big rustic stone‟ to be installed at exactly the same spot on Blaha Lujza Square where the revolutionaries of 1956 had left Stalin's head.

Given the way

monuments are usually designed in the former Eastern block this would be also a

great idea, having a monument which is trying to address questions of memory

itself. However I would also see some kind of danger if the stone would be

installed on one of the historic sites of 1956. Projects for monuments are

sometimes much more critical than their realizations. Which is connected to the

fact that it is much easier to have intellectual discussions about works of art

where you can put forward many points of view, where you don't have a unified

mainstream reading which intellectuals, art critics and artists usually can not

influence any more.

I for example

had this impression during a project of a monument I was involved with as a

curator in Forum Stadtpark in Graz exactly ten years ago. Two artists from

Moscow, Artistarkh Chernyshev and Vladislav Yefimov, had proposed a

25-metre-tall monument for Arnold Schwarzenegger who should been shown as a

Terminator-skeleton in the city park of Graz. We had stated that this monument

made of steel would cost five million Euros and started an international

campaign which let to articles on the project all around the world. This media

installation was perfect to transmit critical comments about pop culture, the

relationship of Schwarzenegger and his hometown, about realistic monuments and

so forth. And the monument was of course not realized, we didn't have five

million Euros. Also, which was quite funny, Mr. Schwarzenegger wrote a letter to

me and asked not to erect the monument and to spend the millions for social

means. But, if the monument would have been erected, I guess, it would have

become the symbol of a provincial personality cult for Mr. Schwarzenegger and

all the other interpretations and readings would have become extremely marginal.

Therefore I find it very good or even better to have this project of a monument or non-monument here in this art space. Here we can discuss it as a critical commentary to the official discourse of monuments in this country or in this region which is - more than twenty years after the political changes in Europe – still coming into terms with it's past.

In Austria we were discussing monuments some 20, 25 years when the discussion of Austria's Nazi past was an extremely hot political topic. But that's more or less over nowadays and monuments and memory are not a big public topic right now. The normalization is good and bad at the same time, but it is a historic fact. In your country however, but also for example in neighboring Ukraine mainstream politics is extremely interested in new heroic monuments or in historic paintings. But these works of official art are usually deeply rooted in the 19th century. The paintings which illustrate the new Hungarian constitution are a striking example for that. Given that background the modernistic and conceptual "stone" we are seeing here is not only a work of art. It can also be seen as an extremely important comment on an official discourse which is leading right now in a very strange direction.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Herwig G. Höller