Ultraviolet energetic space

Erno Marosi

To Klara Kuchta, about the various nature of lightAs every one of us has learnt it once, the light has a double fold nature. This physical phenomenon, most essentially needed in the acquisition of knowledge and in finding our way in the world, escapes the criteria of one-sided classification, and can be identified now as wave, now as quantum, depending on how we are prepared to understand it with theories and means.

The dilemma of light has been introduced to humankind not only by modern physics: the expressions used to identify it define several things, even if these cannot be rigorously separated into different semantic domains. For instance, in Latin, the vocabulary of which continues to live in a number of modern languages, there are two words defining it. Lux, the first, might be translated into Hungarian as világosság (light). The order of God in the Genesis is: fiat lux - Let there be light! There is an ancient pun, possible only in Hungarian, “világ világa”; this is how lux mundi (light of the world) has been translated into Hungarian in the Old Hungarian Lamentation of Maria. This light is of a divine, transcendental nature that fills the lower creation, and which distinguishes it from chaos. The divine order is the model of every human creativity, primarily of the artistic one. Then, there is the awful example, the ironic Lucifer, “holder of light”, archetype of the limits of creative will.

The other word is lumen, meaning candle, night-light, lamp, which refers mainly to the source of light, to some bright object emitting light. The oldest known resources of light are related to fire. The possession of this resource - like in the myth of Prometheus, which is about the origin of the civilization - enables people to gain divine characteristics. This is true, however small and modest these resources of light are, compared to the Sun possessed by God! We cannot imagine what fortune Lorenzo de’ Medici, King Matthias, or even the Sun King, Louis XIV. would have given for the possession of one single halogen bulb!

Light, as a physical phenomenon, has proved to be knowable by rational thinking. Optics, with the help of geometry, gradually disclosed its characteristics, defined the regularities of expansion, shielding and reflection. Optics and physiology have made the processes of sight known. With the help of these sciences, the image proved to be rational, and it became reproducible at any time by means of repeatable experiments. The modern times in making images began after the old magic of making pictures had already passed away. The concept of modern art, too, was born in the moment when the artist’s task ceased to be the mere production of images, and turned to be something beyond that. From the 16th century, the image itself has been called to life by using some kind of technique: perspective, photography and, most recently, various electronic techniques of image making. In modern art, art generally goes beyond mere image making, or even avoids it. For the contemporary artist, light is not just a device of transforming something into image. If so, then the art of transforming, of “light-imaging” is the very object of art.

The destiny of light in art is different. Creativity itself, the creative gesture and the secret of genesis are connected to it. This is somehow the temptation of God, as it is not only about the imitation of the genesis, including the possibility of a temptation like that of Lucifer’s, but also about the evocation of mystery itself.

The sacral world, in the widest sense of the expression, is the claim for building a connection with the transcendent. When looking for sacral, art goes beyond optical rationality, and longs to reach the divine source of light. To give an impression of the supernatural source of light, there have been many attempts in the history of art: representing the unidentifiable or the unusually located source of light (let us think of the light effects of sunrise or sunset, the beams of light breaking through the clouds, the play of the Nordic light), or studying the materials that are shining, phosphorescent, fluorescent, luminescent, or refractive like gems. The famous Platonic cave-simile (where the inhabitants of the cave can perceive the luminous phenomena only by the play of shadows on the wall of the cave, whereas the strong light of the outside world is

blinding them) describes not so much the conflict between sacral and realistic light, but the two possibilities of the sacral world, namely, the mist and the overwhelmingly strong light. The former had frequently been applied to indicate sacral illumination: the mist of dark arches in Romanesque crypts, the refractive, coloured lights filtered through the thick stained-glass windows in Gothic cathedrals, the interplay of light and shadow on the paintings of Rembrandt. On Caravaggio’s paintings, the divine intervention appears in form of a beam of light that sharply penetrates the mist: being a sign of exhortation, vocation, or a will that changes fate. The glittering candlelight with millions of reflections on the dense gilding of the Baroque altars is exceeded by the heavenly light that comes through a hidden window of the dome – like the optical deus ex machina of a theatrical scene discloses the essence as such, or like the blinding lightning of the fireworks. On the contrary, there were, in the middle ages, the bright and clear spaces of the mendicant orders’ churches, or the rationally cold chapels of the Reformation period, or the images of a completely knowable nature during the Impressionism.

Klara Kuchta has been dedicated to the studies of the luminous phenomenon for some time now. My personal experience with her comprises a number of conversations which always concentrated on the questions of seeking the transcendent in the European and non-European traditions, and on their careful consideration. In the possession of modern techniques, what could an artist do today if he or she is to inspire mystical experiences instead of producing mere effects? My principal impression is that what an artist can do today is not about finding new devices, but about approaching the transcendent through self-expression. Therefore, I would not call Kuchta’s works mere experiments in the scientific sense. Perhaps, there is no need for experiments at all. As artistic experiments are always self-experiments: the examination of the phenomena that might take us nearest to our goals. Nomen est omen: Clara, the name of the artist, means bright, after all!Translation: Ágnes Bihari

Krisztina Passuth

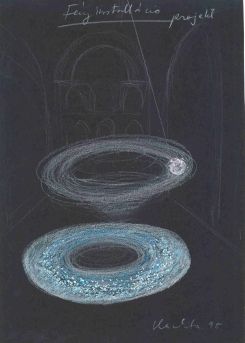

Plan énergétique: light-installation 2004

Klára Kuchta’s light-installation “plan énergétique” (energetic space) was conceived in the Kiscelli Museum specifically for this performance, and it is reborn day after day, minute after minute. Thus, it has no stable or autonomous existence: it is bound to one specific place in one specific period, namely the church and the time of the exhibition. Limited to this quite short period, its existence, at least in the usual sense of the word, is, therefore, more virtual than real.

This is a work of art which could not be transported from Geneva, the artist’s home, to Budapest because there was almost nothing to carry from one place to the other except for the conception itself; some four or five tons of salt, a couple of UV (ultraviolet) strip lights, a sphere made of resin, and three large colour photographs. It is especially true if we take into consideration that a space, as vast as 500 m², is to be filled with the help of so modest material. Material which has to create, there and then, a spectacle that is composed for the given place, material that lives and changes with the place, and that is capable of, or at least gives the illusion of, transforming its environment.

Regular visitors are already familiar with the interior of this church, as it has served as a home to a great number of exhibitions and installations. Always transformed by and adjusting to the particular task it was given, the inner space of this church has varied to such extent from one exhibition to the other that one would not identify it immediately at a new opening. The interior has again changed a lot: its most important task now is to accommodate and to organize an installation built upon the unity of space, time and motion/energy. A trinity that will not be noticed by the spectator directly; he or she will perceive it only indirectly in accordance with the three articulated parts of the building and with the installation they are given. Thus, the three parts of the church, namely the entrance, the vast interior and the apse, have their specific function and are taken into possession by the artist with three different techniques.

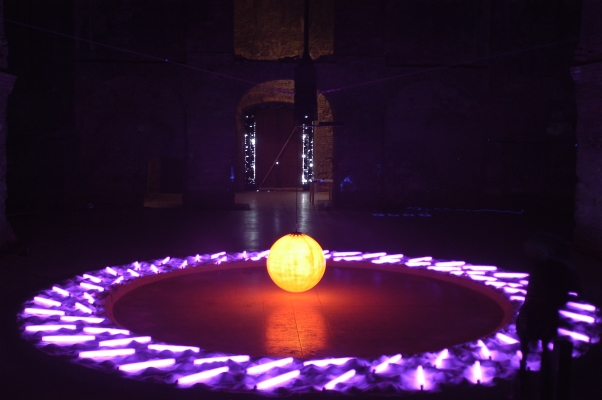

Considering that a grand light-mystery is being celebrated here, it is no wonder that the spectator is welcomed at the entrance by an angel/archangel, represented here in human shape, who is virtually dancing high above, in a DVD projection. This angel, who looks as if it were the materialized image of our own imagination and desire, guides us inside the church, towards the main scene. This is where the real event is taking place: two harmonizing spectacles, an impressively large sphere of light and a gigantic circle of light are responding to one another, while the “black strip lights” are radiating rays of bluish light. This extraordinary sight appears in two superposed planes: one next to the floor, the other a couple of meters above. On the floor, there are tons of salt crystals accumulated and spread out in a disc of 8, 8m in diameter. The mass of salt is surrounded by the “black strip lights” forming a 1, 2m wide circle of light. Their blue radiation fills the entire exhibition hall, and lays a strange emphasis on the aged walls, which, too, seem to become virtual in such unearthly lighting.

Two and a half metres above the ground there is a 80 cm wide sphere of resin that is fastened to a rod and is illuminated with a red light. Unlike the motionless bluish circle underneath, the sphere of light is far from being motionless: it is whirling round 24 times a second. This spiral-like motion recalls in the spectator’s eyes the vision of a red ring, which, in opposition to the earthly cold blue of the UV radiation, gives the impression and delight of a continuous radiation of energy, moving unimpeded in the air, independent from the force of gravity. These two different kinds of light, the cold light radiating evenly from the salt, and the whirling, virtual red light almost entirely independent from the matter, contrast each other. At the same time, they are also complementary and conditional upon one another: the sights of the static and the dynamic, the passive (constantly radiating) blue, and the active red (regenerating and changing in every second) are effective together. The distance between the two images is little, which makes their connection and interdependence manifest. These two forms of light are sufficient to fill the enormous interior of the church. Light and the energy coming from it not only dwell in the space at their disposal, but they also make the otherwise bare and empty space somewhat perceptible and distinguished. Owing to the fact that the light here is not projected on the walls, but it takes shape in the space surrounded by them, it restructures and rearranges the interior of the church, and enhances the original dimensions of the building with a new one.

Klára Kuchta’s installation is completely new of its kind, while it is also adapted to the given circumstances: it fully exploits the specific possibilities given by the museum. At the same time, this work of art is in close connection not only with the artist’s previous works and light-installations, but also with that primarily twentieth century practice and approach, which places motion and light in the centre of its artistic investigation. Thus, Kuchta is related to kinetic art, op art, lumino-dynamics, etc. Interestingly enough, the latter tendency has attracted numerous followers in the middle and eastern European area from its birth up to the present day.

It was in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1967 that the first large-scale exhibition of this issue was arranged by the Czech born, Paris resident art historian Frank Popper, who continued to be the most renown authority in the subject. Popper’s rather comprehensive book, L’Art cinétique, appeared in 1967 and has remained a fundamental work of reference of its field ever since. In the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1983 another exhibition focused on the same subject; it was entitled Electra, and was based again on Popper’s conception. This time, the exhibition introduced the theme of motion and light, and presented the innumerable possibilities of their utilization, from the point of view of electricity, ranging in time from the very beginnings to the year the exhibition opened. In the material of this exhibition, which was extremely rich and unbelievably spectacular, both kinetic motion and play of light had an important role.

Wishing to examine Klári Kuchta’s works “in the light” of these investigations, we might have to reach as far back in time as the year 1920 when the Russian artist Naum Gabo produced the first kinetic work of art, entitled Kinetic sculpture. Immobile wave; this sculpture consists of nothing more than a thin metal rod that, effected by electricity, starts moving, and creates a kind of virtual space around itself. This is the case of Klára Kuchta’s sphere, with the difference that her sphere creates a much vaster space with wider dimensions around itself, and in that her sphere moves in the air, detached from the ground. Apart from Gabo’s sculptures, Kuchta’s sphere must have had another antecedent. Around the same years, the forms of sphere and ellipsis appeared in Russian art, even if in a fretwork structure yet, in the workshop of another Russian artist, Aleksandr Rodchenko. His sphere, unlike Kuchta’s which is fastened to a rod, was suspended by a piece of wire or string, and was set in motion by the air and not by electricity.

If Rodchenko’s sphere was illuminated and was set into motion, it projected drawings of light and shade on the wall behind. Thus, the whirling sphere in Klára Kuchta’s installation has been motivated by these two principles, and must have been conceived in accordance with the different artistic approaches and methods of Gabo and Rodchenko; obviously, Kuchta has been able to make use of a much improved technology of a higher level. The role of the sphere in her installation is just the same as that of Gabo’s metal rod: both are set in action and thus get artistic existence by electricity. Whereas Gabo’s kinetic sculpture exists simply by means of the accelerated motion without any kind of light effect, Klára Kuchta’s construction creates a radiant spiral in the air, by effect of both the light placed inside the sphere, and of the accelerated motion. In the beginning of the twentieth century, the play of light as an autonomous form of artistic expression was more or less related to musical sounds yet. In the 1910s several colour-organs were created: almost all of them constructed by Russian artisans. It was Aleksandr Skrjabin, a composer (and not even a visual artist), whose activity gave birth to one of the first organs of the kind. With his colour-organ, bearing the name Tastiera per Luce, Skrjabin was capable of connecting musical effect with coloured light projection. Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, Skrjabin’s compatriot, started experimenting with similar constructions as soon as 1909; by 1916 he succeeded in bringing his own colour-organ to such perfection that he gave performances of “light-concerts” in various countries. There was another artist, the Czech Zdenek Pešanek, who had also tried to make his own way by finding new paths. The entire artistic oeuvre of Pešanek consisted in connecting kinetics with effects of light: he showed equally great concern in kinetic light-sculpture, in the colour-piano, in the kinetic fountain and in the neon light.

In 1930 the Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy, with the help of the architect István Sebõk, called to life the so-called Fény-tér-modulator (“Light-space-modulator”), Lichtrequisit or Light-prop. This was one of the first works of art which produced a pure play of light, with no musical sounds. This is a construction which is first set to motion by electricity, then is illuminated with various coloured lights from outside, which are thus projected on to a wall or screen. It produces a complex sight: first there is the whirling, glittering structure, pleasing to look at in itself, then the projected coloured lights all around. Moholy-Nagy’s Lightprop served as a source, as a starting point to several further experiments and efforts (like the lumino-dynamics of the other Hungarian, Nicolas Schöffer) from the year of its birth, 1930.

Klára Kuchta’s sphere unites the structure with the virtual effect it produces. The spirally whirling sphere itself becomes the very source of light: the play of light and the structure generating it are not at all separated, whereas they are one and the same, and such unity has a much concentrated and powerful effect.

The other component of the installation is the mass of salt spread out on the floor and the “black neon” strip lights surrounding it in the form of a ring. According to common knowledge, neon was first made use of, as a new device in figurative arts, only in the second half of the twentieth century. There have been two artists who employed fluorescent strip lights in this period: the French Martial Raysse as early as the 1950s, and the American minimalist Dan Flavin from 1963. Flavin made manifest use of these lights: he put and arranged them in a way that the strip lights themselves and the light radiating from them became objects of art, even icons. According to the artist’s definition, these strip lights might have some religious connotations as well.

Contrary to this common knowledge, neither Raysse, nor Flavin can be considered to have been the first to employ neon lights. Much earlier than their appearance, in the 1930s, it was the aforementioned Zdenek Pešanek whose statue, entitled Man and woman, is ideated in a way that the bent neon light not only illuminates the protracted, long-shaped sculpture, but it also becomes organic part of it. Thus, the neon strip light utilized here is the protagonist, so as to assert itself as a self-sufficient object of art, or at least as an autonomous piece of art.

As opposed to this, in the case of Klára Kuchta’s installation, the “black neon”, the ultraviolet strip lights here have a different function: that is, their principal task is to provide that huge mass of salt-crystals with light, actually, with a strange and rather mysterious light. Thus, the mass of salt gets a particular stress; it loses its original properties of a weighty white material, and is enriched by others in return. The spectator will witness a kind of dematerialisation process: the salt has gained energy, and has been transformed into a source of light, a radiating object itself. The technique of transfiguration, or redefinition of given natural elements had earlier been experimented by “land-art” artists; logically, these experiments were realised, and also left behind, in the open air until nature regained them for herself. The case of the present exhibition is somewhat different: here the transformation, or “witchcraft”, does not take place in the open air, but in the inside of a building that used to be a church once, the remainders of which, like the apse or the architectural structure itself, are emanating the same sacral atmosphere as before. In this environment, the existence of this mass of salt that is radiating of itself, becomes mysterious, if not supernatural. No kind of sacral quality is emphasised here in any ways; on the contrary, it seems as if the artist had not at all taken it into consideration, or if yes, she had done it unconsciously. The sacral effect here has not been contemplated directly: it is

born as a consequence of the scientific techniques and of the creative power of the artistic imagination Kuchta has exploited here, and especially of the place’s singular atmosphere. Once it is born, it exists: an ordinary mass of salt is now transformed into a source of light, and is radiating in the middle of the space. Something has happened, or is happening: we witness a fragile, but all the more memorable vision, which has been called into being by the UV strip lights in the interior of a former church. We, the spectators, who attend this transformation, can feel the energy coming from the light, and the bluely radiating beauty of the transfigured material.

Translation: Brigitta Kovács

Last updated February 12 2004