INSTALLATIONS IN THE MUNICIPAL GALLERY

1992-2014

Municipal Gallery / Museum Kiscell,

Templespace

2nd October–16 November 2014

Curated by Fitz Péter és Mattyasovszky Zsolnay Péter

PETER FITZ

Installations in the Municipal Gallery

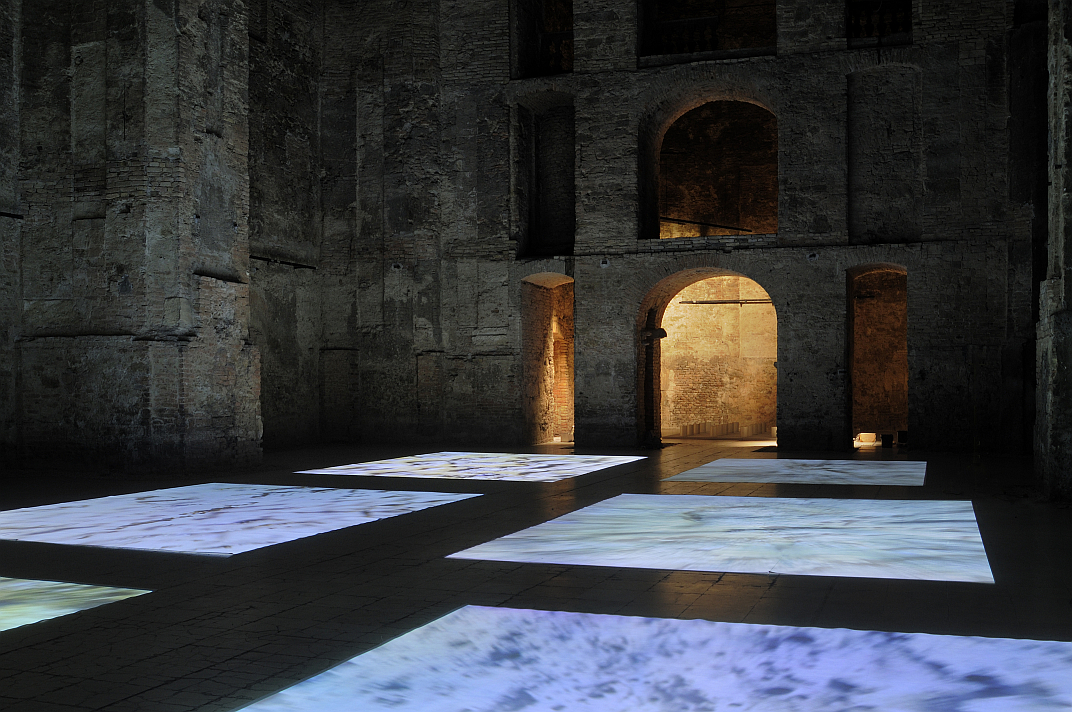

The Templespace of the Museum Kiscell got its final shape in 1992. The re-shaped spot of the exhibition space –

which was also a theatrical and concert hall according to the original intention – was equipped with the highest technology of that age, including underfloor heating, changeable and variable lighting, hooking up on mobile rails, adjustable hanging points for fixing the pictures. At the same time the repeatedly reconstructed interior of the building and the bombed, burnt surfaces with the raw bricks also remained. The original Baroque templespace was rebuild into a three-leveled barracks already in the 18th century, and its shape remained unchanged till the 2nd World War, when it was hit by a bomb, its roof collapsed, the northern walls tumbled down, the building burnt out and was in ruined state in the following decades. The reconstruction, better to say the rebuilding, was extremely successful, actually a never-existed architectural form arose; the triumphal arches of the original, habitual, Baroque structure of the temple, closed with a sanctuary, was already walled up in the 18th century, these held the subsequently built floors. These closed blocks, walled up and structured with arches, partly remained, and became important components of the new space. The wall painting was destroyed a long time ago, instead of it the old – and newer – brick masonry remained. This architectural environment, with a relatively not too big basic area, that is 550 square meters, combined with the large interior heights – the heights of the ridge is 24 meters – produced an extremely imposing space. The architecture, changing many times, can be hardly identified, but it definitely suggests a historical atmosphere, and it unambiguously bears that vicissitudinous history and transformation which happened from the once being of a cloister-temple up to the present state of a contemporary artistic exhibiting place.

The Templespace opened in 1992, the particular bases of

which determined entirely the character of the exhibitions

to be organized here. The basic area of the space is only 550 square meters,

which is divided into three parts – sanctuary, nave, entrance hall – and the

central space is also divided with three pillars at the sides, this way these

conditions determine the possible placing of the artworks. This fascinating

space hardly accommodates to the subsequently placed exhibition installations

and variable, artificial walls. At the same time, it is a first-class spot for

large-sized paintings, art installations, sculptures and also

for video projects. The space is unique in its kind, and

offers a serious challenge for all the artists. Its exceptional effect cannot

be evaded, as it requires works which can fit in with the surrounding and

never compete with it. During the years it has become more and more obvious

that the space-specific installations are suitable the best for this

environment.

to be organized here. The basic area of the space is only 550 square meters,

which is divided into three parts – sanctuary, nave, entrance hall – and the

central space is also divided with three pillars at the sides, this way these

conditions determine the possible placing of the artworks. This fascinating

space hardly accommodates to the subsequently placed exhibition installations

and variable, artificial walls. At the same time, it is a first-class spot for

large-sized paintings, art installations, sculptures and also

for video projects. The space is unique in its kind, and

offers a serious challenge for all the artists. Its exceptional effect cannot

be evaded, as it requires works which can fit in with the surrounding and

never compete with it. During the years it has become more and more obvious

that the space-specific installations are suitable the best for this

environment.

Especially, the first exhibition

of this kind did not originate from the field of contemporary art, but the

presentation of Fragments in 1992 was based on the old sculptures of

the Municipal Gallery / Museum Kiscell. The bizarre placing of the

church-sculptures and building-sculptures – in the niches of the triumphal

arch and the arcades, accordingly in such positions where sculptures were

placed never before in an “everyday”, Baroque church – made it clear that the

space is extremely suitable for presenting installations.

It is also unique that the first real installations, like Valéria Sass’, Hanz Dick Hotzel’s, Hannerlore Landrock Schumann’s presentations, the Land Surveying and El Kazovszkij’s Little Purgatory in 1992 were placed not in the Templespace but both were in the crypt below it. El Kazovszkij exhibited the dogs of the Little Purgatory series and the figures of the Little Olympus series in the niches of the crypt. The raw, a bit tottering stone and brick walls were very space-compatible with the colored – red and black – figures. It was one of the most beautiful installations of the period.

The first, really large-scale installation in the Templespace was Róbert Swierkievicz’ exhibition, the East Begins – West Finishes in 1994. It was the exhibition for sure which made unambiguous that the Templespace is extraordinarily suitable for space assemblages and installations, what is more, the spot inspires the artists and the thematic.

There are forty-eight exhibitions in our summary, but actually the total number is more. Namely, it is extremely hard to define a correct typology for the “exhibition situation” of the space assemblages, spot-specific installations. Several exhibitions are not enumerated in our list, where the general impression, the main direction of the artistic intention does not primarily tend towards the installation. These are mainly group exhibitions, though a work of this type could be on show, but the whole exhibition was not about it. In the 90’ies these were among others the 12 artists from Austria and Hungary (1994), the Myth, Memory, History (1997), The Dream of Existence – Young Japanese Artists (1997), the Plastic Age (1999), then in the 2000ies the Northern Dimensions – Finish Artists (2001), the Re-Consiliation / Megbékélések – French-Hungarian exhibition (2002), the Revolutionary Decadence (2009). In case of the solo exhibitions the distinction is more difficult, as there were nine exhibitions where installations were also on show, but it was not determinant from the point of view of the whole of the exhibition. For example, it was István Lisztes’ sculpture exhibition in 1994, with 12 life-size human figures, which was, independently of the placing, rather a spectacular sculpture exhibition than a sculptural installation. The contrary of it is also true, as there were some works at the presentations which were sculptures by nature, but according to there settings, the situations and the contexts, these could be interpreted as installations. For example, it was Zénó Kelemen’s work, titled Below the Line (2013), though, considering its branch it was a single, monumental sculpture, but it was executed for this space, it had strict formal and spiritual relations with the space, that’s why it is included in the list of installations.

The first installation exhibition, placed in the Templespace, was Róbert Swierkiewicz’ East Begins – West Finishes (1994) assembly. It was a combined type, as there were large-size paintings, soaked in the water of the river Danube, and an installation, put together from giant pine-tree trunks, completed it. The triangle- and rhomboid-shape paintings, placed on the triumphal arches, lifted up the space to the heights. All the components of the assembly referred to each other and the space, this way the different works formed the space to a homogeneous whole.

Péter

Forgács: Inventory (1995) exhibition was the firs video

installation. It was a complex work, which did not care too much about the space, but rather the artist

projected his own video installations in the space used previously as an

exhibiting space, this way the effect was different than it could have been in

a regular white cube space. The central piece of the exhibition was the

Totem, which presented the story of pig-killing in a reversed order, that

is it started with the final state of sausages and white/black puddings to the

original state of the pig by reassembling it from parts. The video monitor was

watched by a stuffed pig. The other installation was the Totem and taboo,

which was followed by the “Énke” video and its joining, everyday

objects in the central space.

Péter

Forgács: Inventory (1995) exhibition was the firs video

installation. It was a complex work, which did not care too much about the space, but rather the artist

projected his own video installations in the space used previously as an

exhibiting space, this way the effect was different than it could have been in

a regular white cube space. The central piece of the exhibition was the

Totem, which presented the story of pig-killing in a reversed order, that

is it started with the final state of sausages and white/black puddings to the

original state of the pig by reassembling it from parts. The video monitor was

watched by a stuffed pig. The other installation was the Totem and taboo,

which was followed by the “Énke” video and its joining, everyday

objects in the central space.

Considering the type of Gyula Konkoly’s exhibition in 1995, it can be compared with the form, initiated by Swierkievicz: there were large-size paintings in the walls, to which the artist shaped the space, filled up with monumental sculptural objects. In the central axis of the space the artist formed a shallow pool from black foil, in the water of which a gigantic, painted, carved plastic cube mirrored. As a counterpoint, prisms, tomb-stone figures, carved from the same material, were placed in other parts of the space. He succeeded in making harmony between the paintings and the forms of the accidental installation, though the spiritual connections were not as strong as in the case of Swierkievicz.

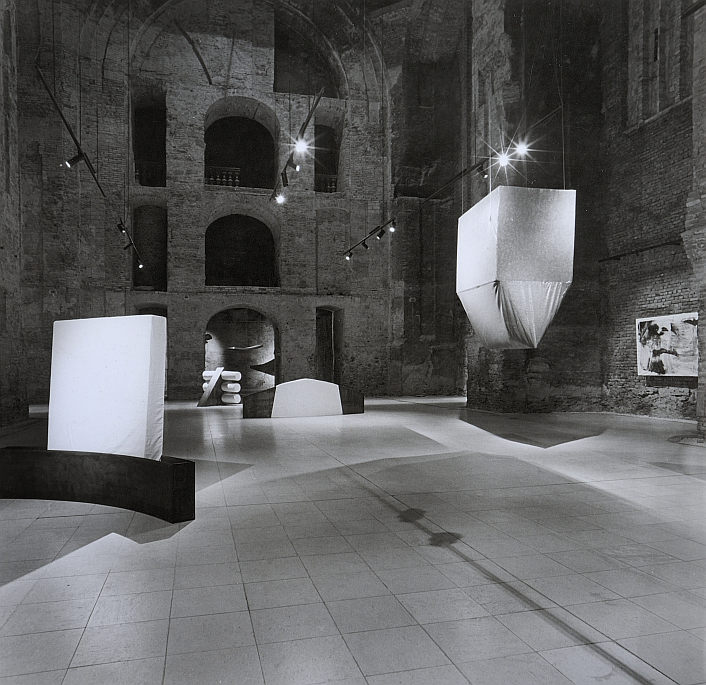

György Jovánovics: Ut Manifestius atque apertius dicam (1996) exhibition was a very particular one. He was the participating artist in the Hungarian Pavilion in the Venice Biennial in 1995, and our aim was to present the original concept to the Hungarian public, too. It was the other, essential task of the exhibition in the Templespace, because his “spot-specific” installation in Venice, which referred to Giorgione’s Tempesta, fundamentally remained undiscovered, meaningless to the foreign public. Therefore, this installation intended to present the Venice conception in the shape of a concentrated explanation. The title referred to it as well: Ut Manifestius atque apertius dicam (I say it unambiguously and clearly).

The video manipulation, projected in large size in the sanctuary, was the animation of Tempesta, in which the figure of the guard made a move from time to time, and told that it is Giorgione’s picture, the Tempesta. A part of the installation, titled Detail from the Big Tempest, was also a sculpture standing before the projected picture, which represented the partly destroyed fragment of a column from Giorgione’s picture. The Big Prism stood in the nave of the Templespace, which is also built on the motive of a form of a building in the original painting.

Dóra Mauer – Zoltán Szegedy-Maszák: In the Stomach of the Whale (1996) exhibition was the joint presentation of two conceptions of different characters. One of the motives of the installation assembly were the projections of Dóra Mauer’s paintings about the curves of space and its joining spatial forms, while the small installation of everyday objects, e. g. bottled fruits, her S8 films and video materials, her slide series, the Chamber, and Zoltán Szegedy-Maszák’s sound installation.

B. István Gellér: Finding (1998) installation was the newer presentation of the artist’s Growing City art project, which was consequently built from 1979 on. It was the presentation of the components of a fictitious city, the installation combination of new connections.

Mária Chilf and Gábor Szörtsey’s Under Tulps Sky (1998) exhibition belongs to the first type of installations – applying already existing installations to the given space – with the variation that the pictures, presently the large-size drawings on paper do not originate from the installing artist, but from Gábor Szörtsey, altogether they were in harmony with Mária Chilf’s objects in one installation. Chilf’s surreal shower-bathe tray with the network of floating, plastic veins of blood and Szörtsey’s minimal objects, floating in the space of nothing, brilliantly completed each other.

Imre Bukta: Walk in a Space without Blessing (1998) minimalist installation was expressively made for this space. The anti space-assembly, based on the spirit of the space, was executed the way that from the Templespace itself almost nothing could be seen, being absolutely dark there, one could only feel – and know – that we are in a enormous and high place. In the midst of the floor of the hall a ray of light of thirty centimeter wide spread, on which a very tiny, five centimeter long and three centimeter wide, sledge was moving up and down in the total length of the ray of light. There was silence, only the creaking of the sledge on the stone (on the snow) could be heard.

Balázs Kicsiny: 23 Sailors (1999) is the first and emblematic work of the artist’s large-size installation series, which determined to a great extent his additional activity. The previous thematic of miners was combined with the motive of sailors, the figures of hammerpick-anchor-armed mariners covered the whole space, while lights radiated only from the miner’s lamp placed at their hands. The Templespace was a monumental burial-place or the group of figures falling on their knees for worship at the same time.

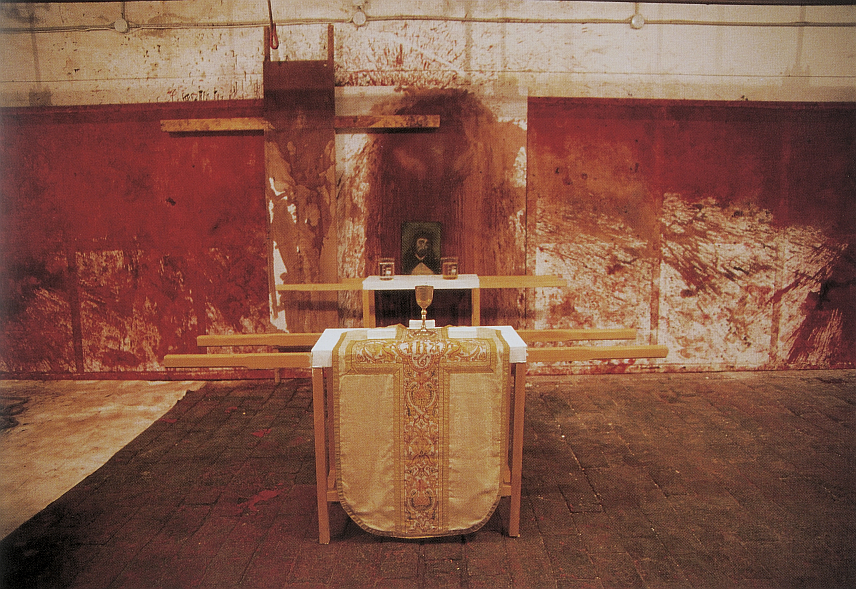

The preparation of Hermann Nitsch’ exhibition, the Six-day Play in Prinzendorf (1999) took two years. The stage properties and documents of the mystery play, taking place in Prinzendorf in 1998, was first on show in Vienna, in the Liechensten Palace in the Museum der Moderner Kunst – Stiftung Ludwig in the spring of 1999, then the assembly of objects came to the Templespace of Kiscell. According to the bases of the place, the material was a bit crammed, but the once place of the church was a very suitable spot. The installation in the nave, which walked round, the altar-like setting in the sanctuary proved very attractive. After the change of the system this exhibition became the first remarkable “cultural scandal”. There was never an exhibition like Nitsch’ installation with such a nation-wide attention.

Sándor Pinczehelyi also exhibited in 1999, the main motive of which a long

table was, spreading in the midst of the hall. The artist put on the table

different, painted, emblematic motives and the herd of swine with the pigs

painted red-white-green. Certainly, it was completed with paintings.

The decade of 2000 brought the golden age of installations in Kiscell. In these years the artists have tried to work especially for this space, so their exhibitions became place-specific.

Ágnes Deli’s installation (jointly with Zoltán Bánföldi’s pictures) was based on the pair of opposites of soft and hard, manifested in her sculptures. The space was ruled by an enormous, golden house-like form, hanging upside down, the mass of which was executed from foam-rubber, and was covered with shining, gleaming textile. The seemingly heavy form was floating easily in space, making a dialogue with other objects, the light-heavy sculptures, combining metal and soft materials

Károly Halász: Pictures Trampled Underfoot (2000) installation arranged the old and new pieces of his series of his painting, also titled Pictures Trampled Underfoot, into a new context, as he placed them onto the ground in the position these were originally executed – trampled and fixing the footprints – completed with the objects of journey and wandering (bundle, pack, stick).

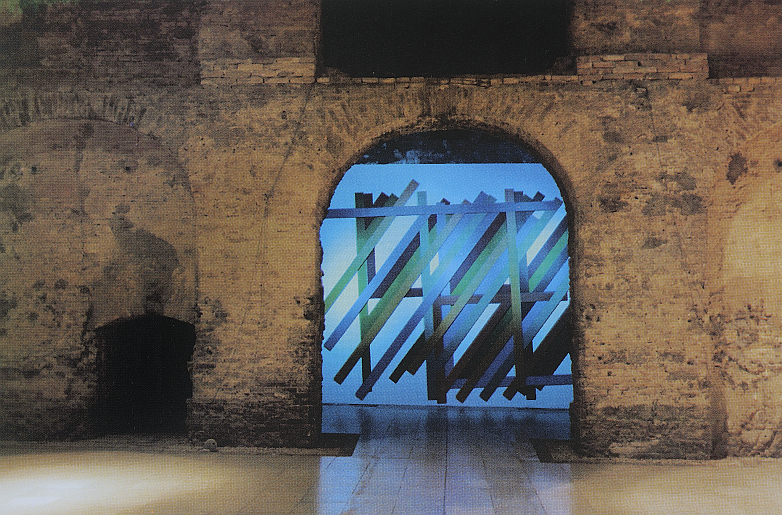

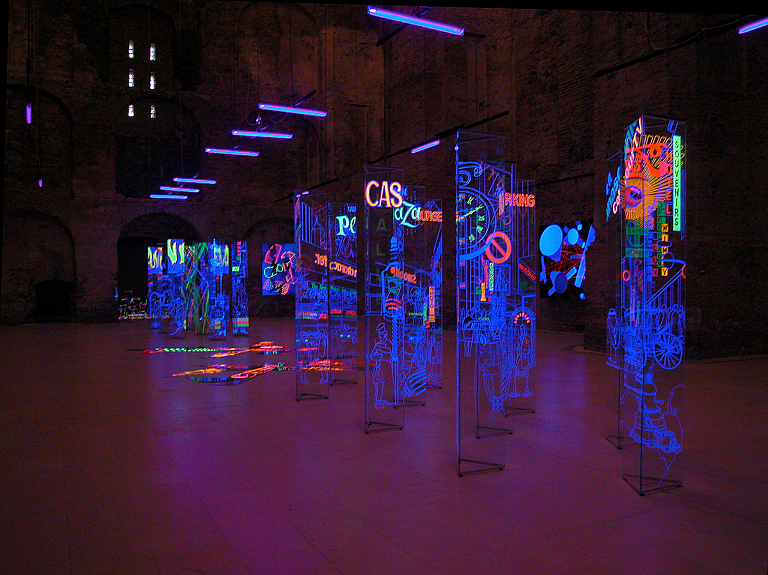

András Mengyán’s exhibition, the Magic Transparency (2003), which is an installation of lights, mirroring, UV effects, was expressively made for this space. The basic principle of his works is permutation without repetition, the representation of space and time, different dimensions. His paintings, got to life in ultra-violet light, are also the organic parts of his large-size, many-parted installations.

Barbata Laura Anderson: Mythic Journey (2003) covered the whole space, organic materials ruled the assembly, leaves covered the floor, and the solo works, as parts of the whole, were executed from natural materials (maize-ear, wood, flax, bamboo). The object assemblage, starting from Indian tribal art, with its mystical messages, with its nearness to nature, had a very particular position in the series of installations presented in Kiscell.

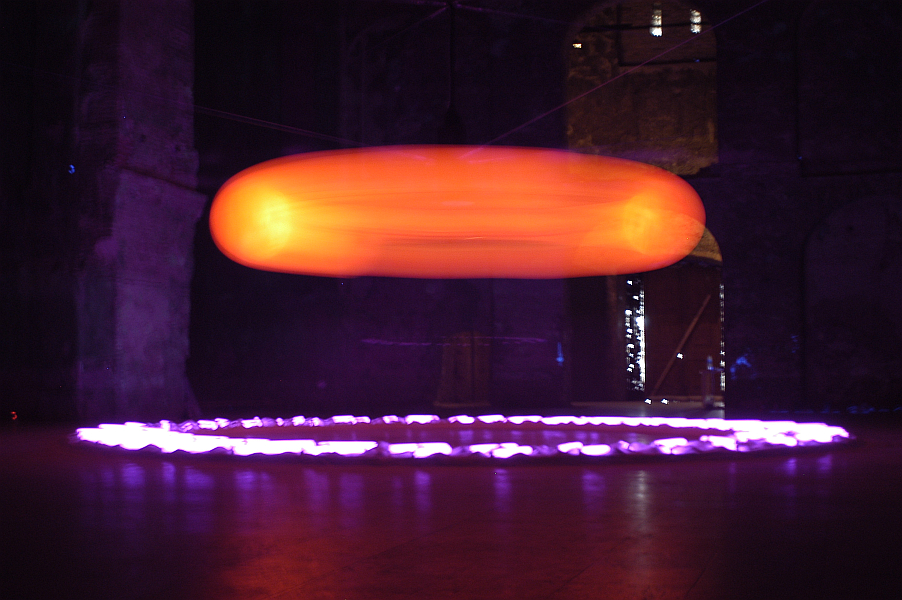

Klára Kuchta’s Ultra-Violet Energetic Space (2004) was from among the installations executed expressively to this space. Certainly, she brought to life this work on the basis of her previous activity, at which she examined the behavior of light and its positions in move. It was a circle of salt, the diagonal of which was six meters, with neon tubes radiating UV light. Above the centre of the circle a large-size, orange-colored ball was hanging, which was rotated by motor-driven mechanics.

In the decade there were three group exhibitions, installations in the Templespace. It is always a more problematic task than the cases of individual constructions. It depends on the common conception of the participants – if they have it at all – or on the curator. From this point of view, the three group installations represent three different solutions. The first exhibition, put on show in 2004, was the Visible or Invisible by the Block Group, which is a good example for a unified, creative conception, where the agreeing artists, get used to each other, brought to life a homogeneous artwork, though it was different in its details. The second group exhibition was the Folyóparti kapcsolatok / Wired Banks. In this case the seven Dutch and seven Hungarian artists worked for the same word of calling – water-connection –, though it was less homogeneous as an installation. The third type, the Utopia Transfer (2008) belongs to the installations of curatorial type, where the Dutch and Flemish artists jam-packed the space, although it was an astonishingly uniform, unbroken assemblage by the curatorial help of Barna Bencsik.

Balázs Kicsiny’ installation, the Interview in the Pump Room (2006) is an exceptional case from more points of view. Kicsiny exhibited in the Hungarian Pavilion in the Venice Biennial in 2005, and we wanted to show the project of that place to our public. On the other hand, the Interview in the Pump Room was a new project, made after Venice. Already in 2005, parallel with a cultural conference in the Palace of Arts, Kicsiny exhibited his work, titled Pump Room. The reception of the conference was organized in the installation of the kneeling divers, about what the artist made a video, and this new work completed the Venice material. Finally, this new project was practically the “dress rehearsal” of two future exhibitions in New York in 2006.

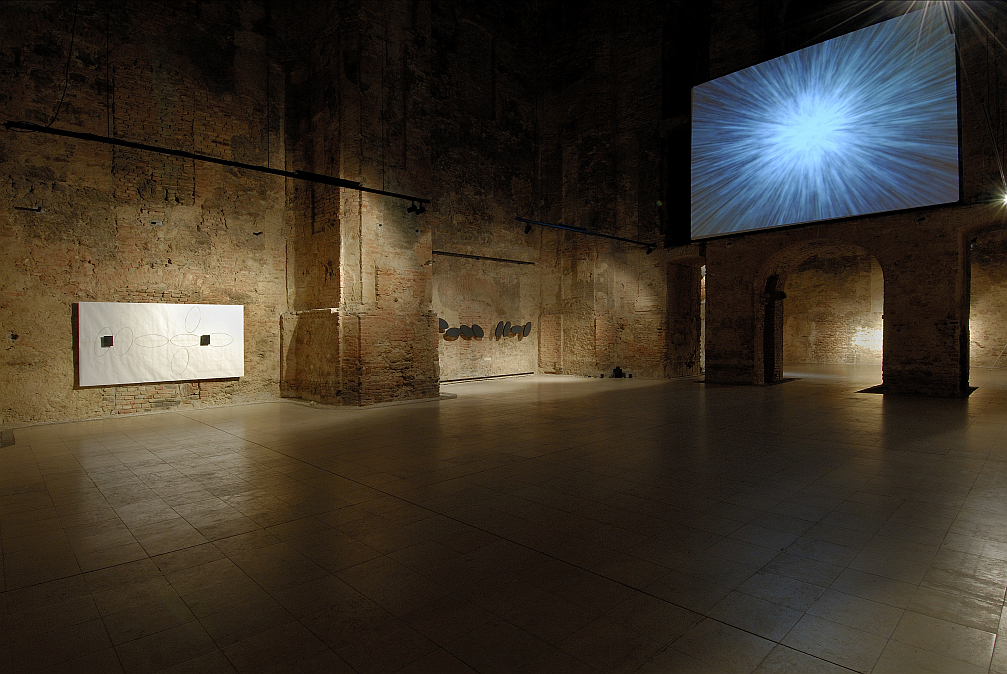

Magda Csutak in her Identical – Independent (2006) work combined the minimalist pictures with astronomical ones, appearing in an enormous projector, representing the spiritual connections also visually between these components.

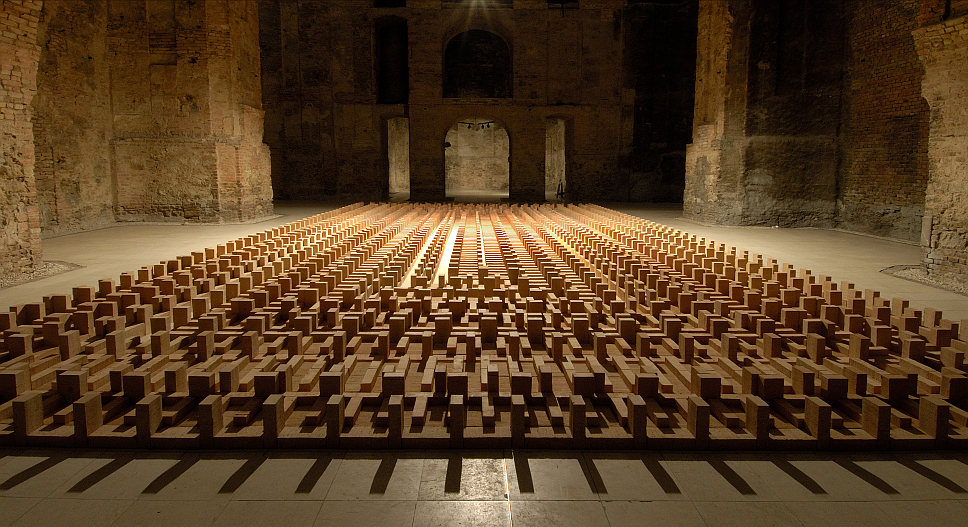

Péter Türk’s Length, Width, Heights (2006) work was one of the most spectacular spot-specific installations. The monumental raster screen, taking out of bricks, filled the nave of the Templespace, its relief of minimal heights – executed from standing bricks – pulsated fascinatingly in the whole space. In the Municipal Gallery it was Türk who realized a single work which cannot be repeated.

Gyula Várnai’s installation, titled One of the Rare Moments (2006), is characteristic of the same singleness and strict constraint. Its central piece is a model of a temple, from the holes of which light rose, and this way it projected the forms of the interior to the forms of the real building. The model of the temple was hanged up, swinging gently, this way the real architecture seemed to move as well. In the sanctuary fragile objects of light made the whole installation project balanced.

Josef Bernhardt’s Birds (2008) installation is, one the one hand, the continuation of the oeuvre, of his central artistic idea, while on the other hand the central part of the project was expressively done for this exhibition. The nave was filled up with the forest of large bird cages and boxes from corrugated cardboard, which lined up in strict order. In the sanctuary different requisitions, referring to the coexistence with birds, are lined up, e. g. portable feeding-tables as symbolical rucksacks, birds as scarecrows, thorns against birds.

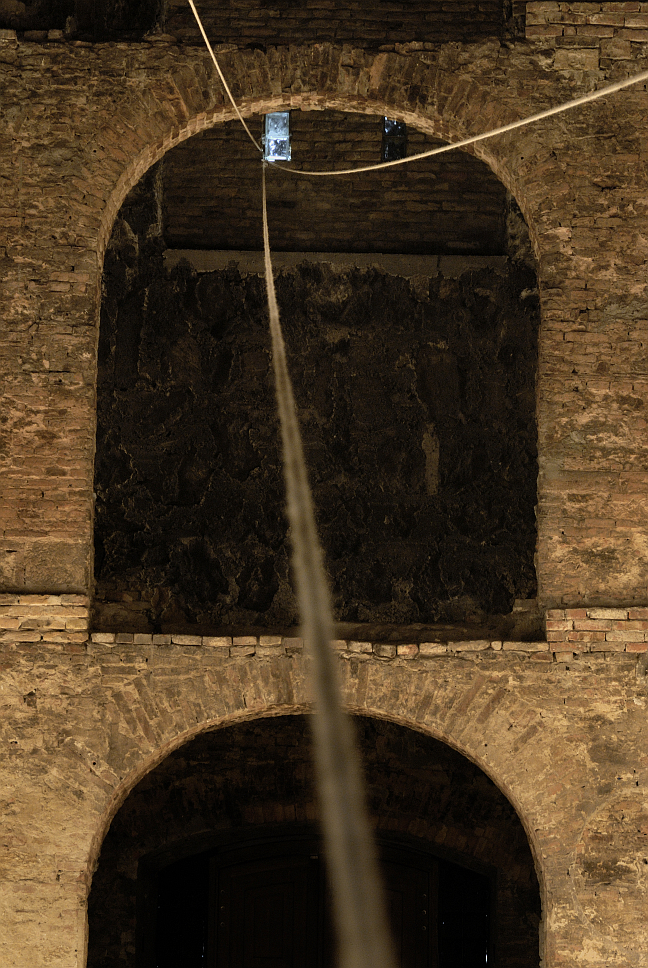

Mimmo Roselli’s minimalist installation (2008) includes altogether two hawsers, the positions of which determined and crossed the space. He fixed the hawsers outside the Templespace into the ground, from where these came in through the little windows on the floors, then, crossing the triumphal arch these ropes moved through the Templespace and finally were jointed to the wall of the sanctuary. The two hawsers redefined the space.

Kis Varsó’s Two Pieces (2009) installation had two parts. One of these was the “Fools’ Ship” film project in the co-production of Manifesta and ACAX, made jointly with Miklós Erhardt. This was on show in the nave of the Templespace. The other part of the installation was a project about publication, which applied the archive of Kis Varsó by the Innen independent publishing house. It was placed in the apse. It was the exhibition when conceptual installation appeared the first time in Kiscell.

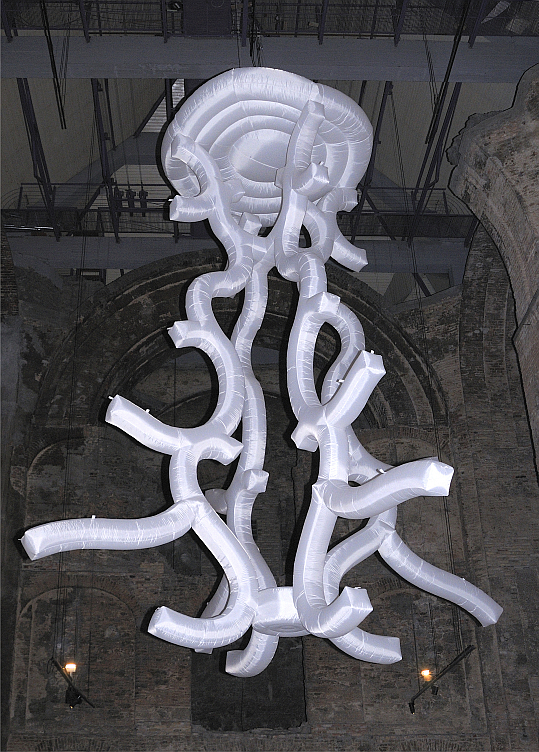

Orshi Drozdik’s Un Chandelier Maria Theresa (2009) installation was based on an idea. All the components of the quasi reconstruction of a chandelier from the age of Maria Theresa was on show in the Templespace and the Oratory. Drawings, small- and large-size models, then the enlarged structure of the chandelier became the finished work of art. It was executed from plastic, and from time to time a programmed ventilator blew it up and made the rubber chandelier go down.

Hajnal Németh’s Collapse – Passive Interview (2010) was a particular installation. It included a black BMW car, crashed in an accident, and a sound installation, which was arranged around the remains, this way it was so to say in quotation marks. The six-channeled sound installation elaborated the stories of car accidents on the basis of making interviews with the suffering persons, the text of which was set to music and it could be heard in the Templespace in the performance of three singers. Red lighting belonged to the dramatic situation, while the text of the oratorical work could be read in the music-stands

It became consciously unambiguous from the 2000’ies that the Templespace of the Municipal Gallery / Museum Kiscell is absolutely suitable for the presentation of space-specific installations. It could be measured as the number of exhibitions increased from year to year, more and more artists accepted the challenge, even those ones who previously never or rarely made installations.

Rimer Cardillo’s Cupí (2010) is a building, which was named after the piles of man-sized hermits. Cupí raised the death cult of the local aborigines. Rimer Cardillo built three piles of ground, which were covered with ceramic masks, fossils, tiny objects of remembrance.

Eszter Csurka’s Desire (2011) installation was a very complex work. The artist, who is a painter basically, put on show only some pictures and she applied to it a very complicated assemblage. She covered the floor of the Templespace with black foil and filled it up with water. She built pavements into this water-world, lit from below, this way from these components one could see the paintings. Sculptures, spurted from metal, were standing in the water, and at the end of the hall a poetic video presented how the sculptures were done under the water. In little glass-cases there were placed metal jewels as well.

Zsuzsi Csiszér’s Passage (2011) is one of the most fascinating installations in the Templespace, though the artist is primarily a painter. A railway-coach of a passenger train of real size buried itself in the floor of the hall. The back bumpers of the illuminated, partly sunk monster run up to five meters heights. In the sanctuary railway information boards were rolling in the video projection.

Tamás Komoróczky’s Escape Attempt (2011) installation included three, simple components. The neon text of Failed Symbol illuminated in the space on the peak of an enormous platform, on the other side of the hall there were museum objects – fragments of sculptures – exhibited on metal shelves, and behind these a neon flash of lightnin illuminated in zigzags. In the sanctuary a video sound installation was on, while its visual component was the motive of a sea-fossil.

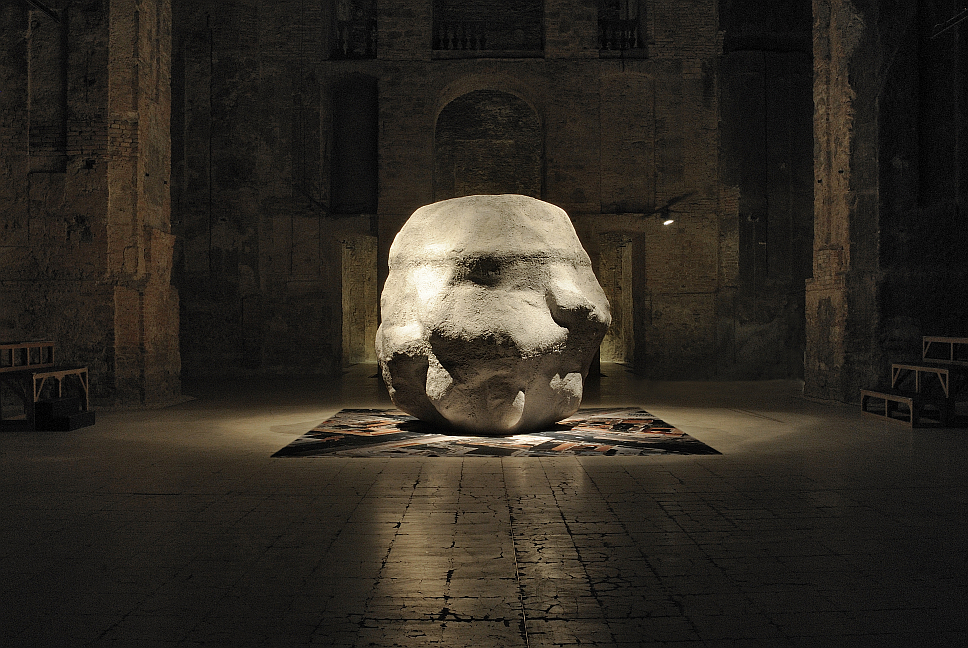

János Sugár’s Fire in the Museum (2012) project was prepared for years. Originally, as the title suggests, it could have been an act of laying a fire, guarded, fed and communicated by a community. It could not be executed because of technical and safety reasons. The Monument of the Mob installation was done instead of it, which is a “big, rustic, stone”. Certainly, it was executed from paper, and could be seen from two, carpentered wood grandstands. According to the artist’s idea it was a monument of 1956, which had to be placed in the middle of the Blaha Lujza square. Both of the conceptions were documented in the exhibition catalogue.

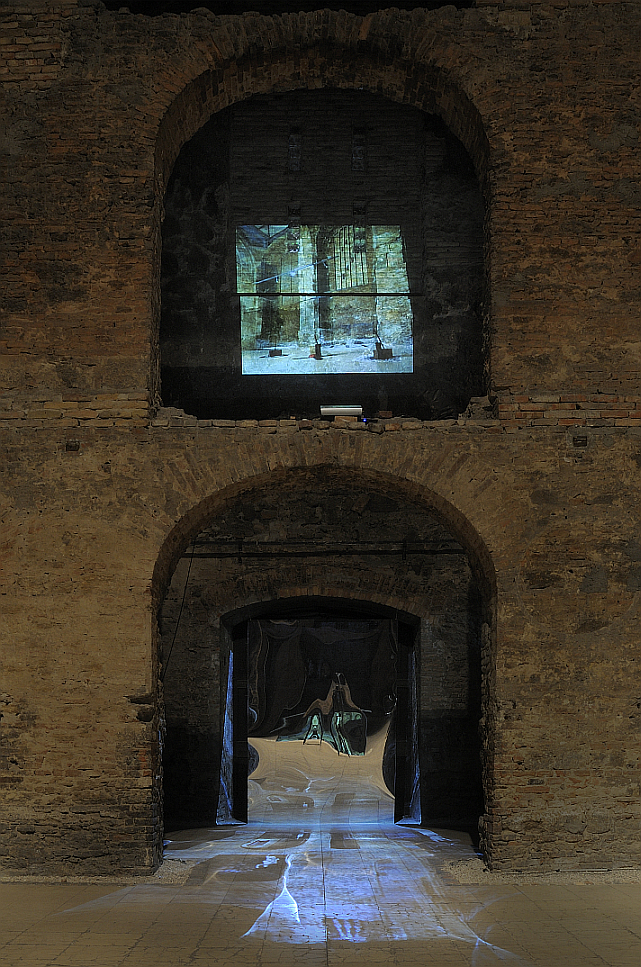

Eike’ Proclamaton (2012) installation was built from three units: the first was the Proclamaton, a particular machine, the keyboard of which can send messages, proclamations by a construction, radiating light signals. The second unit is the Alteration, which is a landscape projected by 6 videos on the floor of the Templespace. There are the surface of the moon and a desert landscape with very slow motions which filled the central space. The third work is Scan, a system of barricade of thorns, which is rhythmically swept with an ultra-violet radiation of light, coloring red this part of the hall.

János Bér’s Consoler of Kiscell (2012) is the exhibition of the artist, living in France, who made monumental canvas paintings for the present show. The striped, large-size pictures have always been typical of his activity, but he never tried to examine their effects in such a dimension. The seventeen meters long canvases, like gigantic flags, divided and determined the space.

Villő Turcsány’s Pendulum Tuning (2012) project was originally a

space- and

sound

installation, which was only partly realized at the exhibition. Four

large-size balls were swinging and shining metallic in the nave.

Computer-driven mechanics operated the pendulum motions of the balls,

accelerating and slowing down, referring to the relativity of time. In the

sanctuary three little balls were hanging, which could be moved by the

visitors. The sound effects were produced by the rubbing of the balls.

Endre Koronczi’s Plobuter Park (2013) installation was the

poetic-visual project

of

environmental pollution in four acts. In the sanctuary the overture could be

seen in several scenes on a monumental video projector. In the nave the mass

of colored nylon bags (86 pieces) were hanging, each of them was moved by

little ventilators, this way the field of bags were rotating, floating. Two

videos, one version could be seen on a monitor, while the other one, projected

onto the raw brick wall, showed the episodes of the nylon bags, chased by the

wind.

Szilárd Cseke’s We Move Abroad (2013) installation was built from important and superfluous objects, the requisites of life during changing residence. All the objects, unpacked in a wide circle, are the deposits of life: clothes, furniture, trash, junk, cheap plastic toys, books, old university lecture notes, paintings, old electronic sets. That’s what remains after we leave. In the inner outline of the circle, directed by crush barriers, different balls were running round about, knocking each other, pushing the other balls to new directions. Among the odds and ends ventilators blew the wind, and the train of air made move the little balls. Job advertisements in English could be read on the outer outline of the circle. In the sanctuary an enormous machine was panting and blowing, while in the other end of the Templespace a cypress stood in a large-size sheepfold, which could be moved by hydraulics, so from time to time the visitor could lift it up with its roots by pushing a button.

Zénó Kelemen’s Below the Line (2013) project is a monumental sculpture,

executed expressively for this space. It may raise a question: is it an

installation or not? If we examine the connection between the work of art and

the space, it can be accepted, over the three-dimensional and graphical values

of the work, that it worked as a space-determining component, which allows

this sort of interpretation. The surface of the form, similar to the Moebius

ribbon, is shaped by graphite shading, which gives a metal-like, shining

impression. The large form ruled the space, and the bizarre shadows of

lightning increased the effect of the work.

Csaba Filp’s Data est defectus – Absence is Given (2013) exhibition

suggested a peculiar, archaic atmosphere. There were non-curtain curtains,

half-armors, angels standing on columns, monumental table-show-case, decorated

with angels, having buckles inside, which were about connections and joining.

Csaba Filp was already known as a painter, but the challenge of the space made

him realize an installation.

Luca Korodi’s Elementary Particles (2014) exhibition is similar to the previous one, as she is primarily a painter, so she displayed paintings in the sanctuary. However, in the nave there was only one, large installation, which showed the relief map of Antarctic, put together from glass crocks, and a hanging projector produced the picture of Antarctic on the glass surface. Ultra-violet light illuminated the landmark, this way the whole object was shining in a peculiar light.

Tamás Jovánovics’ Swing Out (2014) exhibition is the result of a very consequent painting program: he is concerned about tiny motions, the gentle movements of lines. Stepping out from plane to space is the exiting field of his painting activity. This process was presented in the paintings placed in the sanctuary. His works first emerged from plane in reliefs, then in the nave nine red and white, spirally striped columns rose and disappeared high. The row of columns had a slight curve, which gradually bent and tilted from the vertical order. The material of the columns – the visitor could not guess it for the first sight, only when he approached those – was the row of plastic ribbons which were applied at road-constructions and buildings, and these red and white striped, partly transparent ribbons were fixed onto annuli in eighteen meters heights. The stripes of ribbons were fixed strictly side by side, so red and white, spiral forms of columns came to light.

Mariann Imre’s Transience Seized (2014) installation joins strictly to the consequently minimalist oeuvre. In the centre of her activity there is the search for new environments and making new connections referring to the very tiny, everyday signs, scribbles, embroideries, etc. Her exhibition at Kiscell followed this conception, too. In the entrance hall of the sanctuary there was the Transience Seized, a wooden table, while a colored concrete embroidery in it gave the title and start of the project. In the nave of the Templespace she built up a part of a room of her studio, and in its wall the gentle signs, concrete embroideries as scribbles kept on. The closing part of her project was her sketch-book, placed in a little niche under the tower.

Anja Luithe’s Running Around (2014) installation involved eight

brick-red figures. The figures were actually only clothes, the outer

armor-plating of human appearance, in the strictest sense of the word these

were rigid, the pleats and bends were fixed. An electronic instrument,

equipped with motion sensor, made the figures move, nearly dance, if the

visitors stepped in the hall. Their motion is angular, their dance is ghostly.

Anja Luithe’s Running Around (2014) installation involved eight brick-red figures. The figures were actually only clothes, the outer armor-plating of human appearance, in the strictest sense of the word these were rigid, the pleats and bends were fixed. An electronic instrument, equipped with motion sensor, made the figures move, nearly dance, if the visitors stepped in the hall. Their motion is angular, their dance is ghostly.

Curiously enough that the series of the installations in Kiscell did not start in the most suitable place, that is the Templespace, but in the crypt, and at the end of the above-mentioned series, it ended in the exhibition room, named Oratory. The almost fifty installations unambiguously indicate that the spots in Kiscell nearly wish and want the artistic solution of thinking in space. Certainly, we cannot say that the most important spot of installations, let them be national, and partly international, is the Templespace, but its role cannot be negligible.

Certainly, spiritually and formally several assemblages were on show, originating from the oeuvres and activities, and there were some expressively executed for the given spot and there were “marginal cases”, too.

The Installations in the Municipal Gallery 1992-2014 exhibition, and the joining book, tries to document this activity. The conceptions of exhibitions and collection of the Municipal Gallery / Museum Kiscell are strictly connected, as those artists are invited to exhibit, from whom the museum intends to purchase works of art in order to enrich the collection. These artists have got important achievements in the contemporary art scene, and some of their works can be adapted to the virtual arch which determines the collection of the Municipal Gallery. Concerning the installations it is quite problematic, for the very technical reason, too. This way, from among the installations many a time another works got to the collection, which can be managed “more easily” from the point of view of museology.

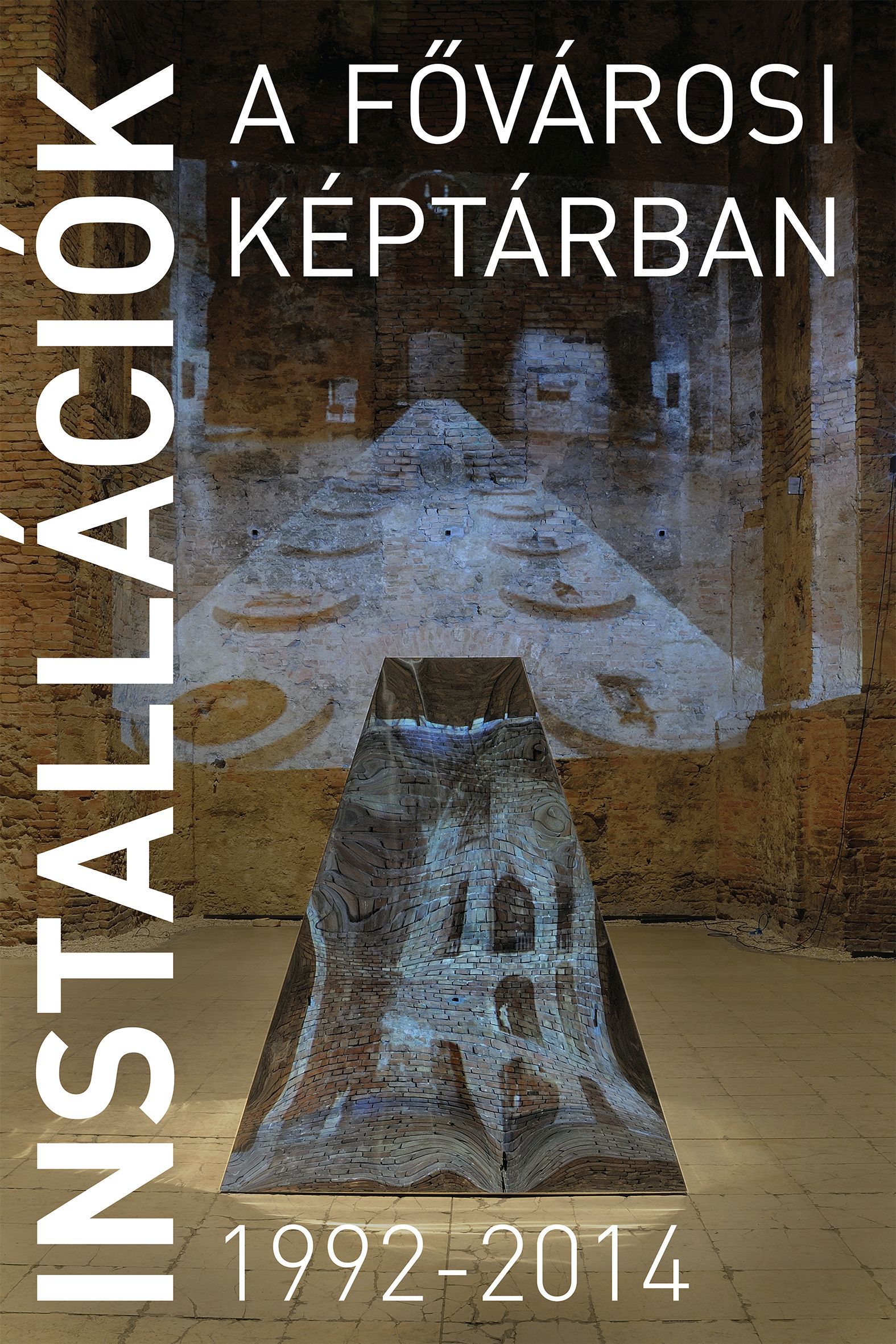

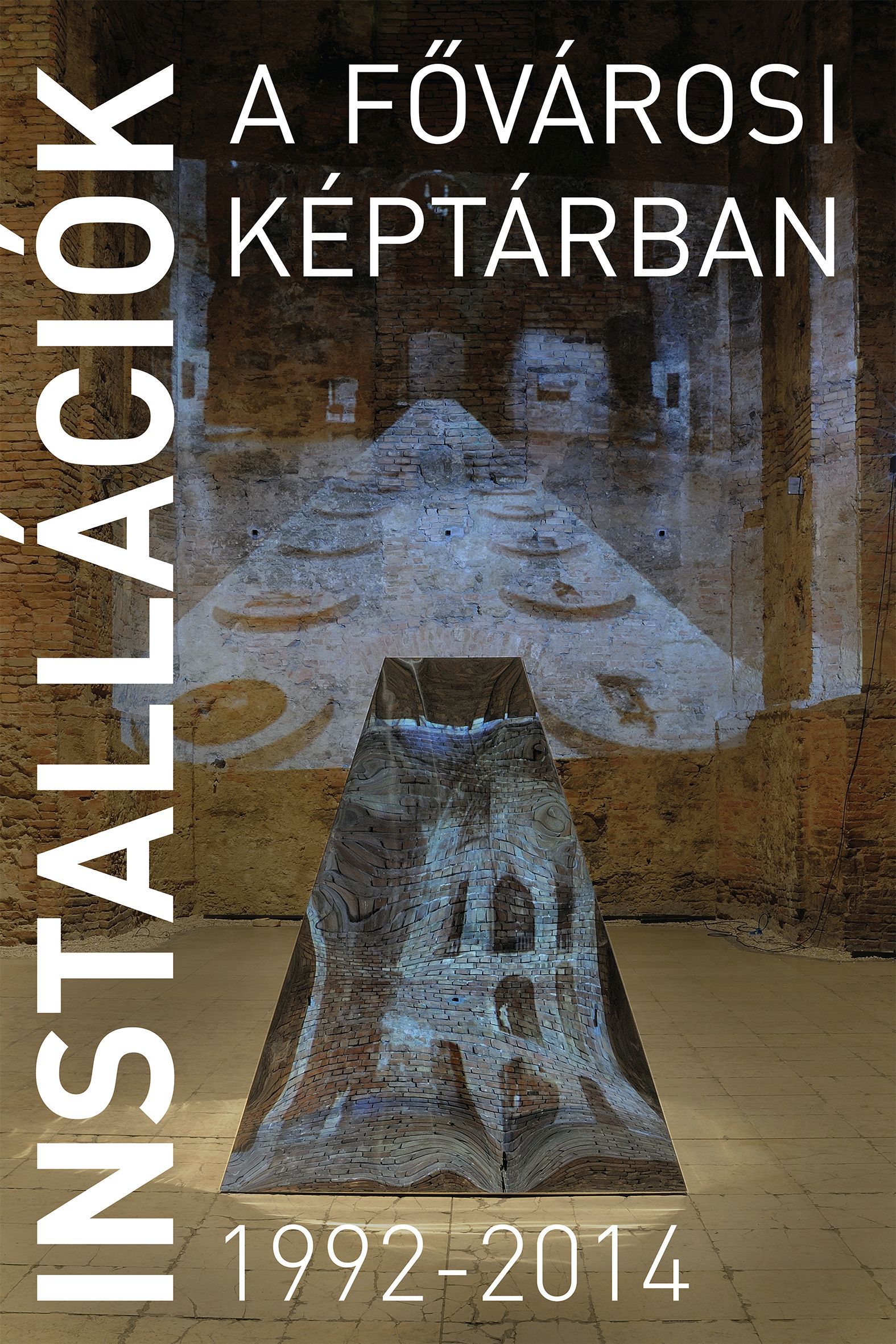

The present exhibition material is actually a documentation, though it is

impossible to line up 48 assemblages. That’s why the exhibition itself is an

installation as well, while five projectors show the photo documentation of

the forty-eight installations on the walls, on a mirror pyramid and on a

screen.

An era is closed by this act, the curators, Péter Mattyasovszky and Péter Fitz

retire. Hopefully the successors will continue the program of more than two

decades, giving space to newer installations in the spot of the Municipal

Gallery.

(Translation by Csaba Kozák)